Siobhan McLaughlin brings her piece Standing Stone/Oil rig to the SEE HERE NOW exhibition. The work asks ‘what do we really see when we slow down and how can this help us care for our land and each other?’ Read on for more.

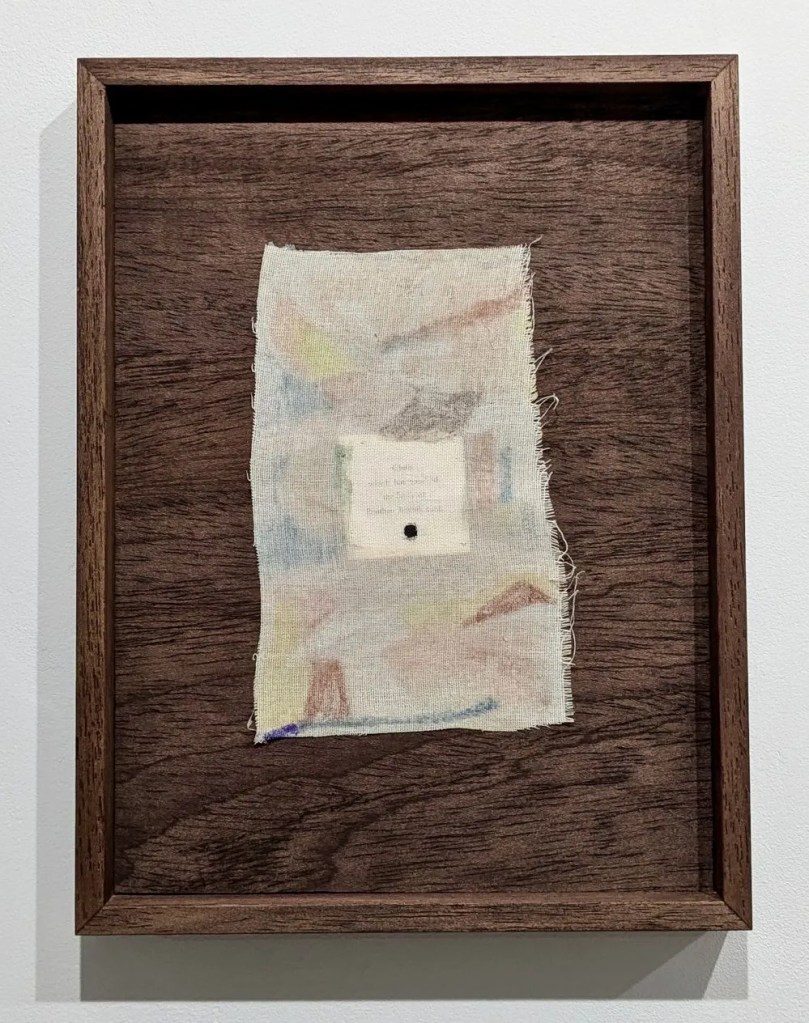

This work considers land use and mineral extraction, as well as mending and care at a bodily scale. It is made from paintings woven with remnant textiles gathered from the landscapes and communities I meet.

Earth gathered with care from Cornish mining run-off is ground into paint to form the image of a decommissioned oil rig on the Black Isle, where the Cromarty Firth has become a kind of graveyard for decommissioned structures.

By using a material palette so connected to the earth, the work asks ‘what do we really see when we slow down and how can this help us care for our land and each other?’.

The following text is an excerpt from Belongings, a piece by Martin Holman written in response to McLaughlin’s show Pilgrimages at Hweg gallery, Penzance 22nd November 2024 – 11th January 2025.

‘If you aestheticise too much,’ says Siobhan McLaughlin, ‘you risk ignoring landscapes for their ecological, social and labour values.’ While toil is not the main subject of this artist’s work within the genre of landscape painting, the presence of labour is nonetheless a notable feature. She approaches the task of making imagery by realising in materiality her visual experiences of the external world. They become manifest through the acts of seeing, touching and being. McLaughlin describes her objective as creating non-traditional landscape painting. For her, that means deviating from the quintessentially British tendency to romanticise the ‘view’ or the ‘experience’ of nature. Because historically ‘landscape’ has been perceived in many instances as a visual salve. The result has been, and I imagine McLaughlin will agree, that notions of the ‘land’, as a product of constant movement by nature and man, has been lost – or, at best, downplayed.

By contrast, her images are constructed with an interrelationship of means. Material layers seem to correspond with physical sensations. We might recognise in the complex edges and surfaces of her work our own encounters with a dramatic natural environment. That experience is inevitably fractured and multidimensional, made up of air, land and sea and the visual tapestry of the piecemeal subdivisions. Mankind has parcelled land into fields and moors, and altered borders to suit changing needs and ownerships, so that echoes of previous patterns remain as vague imprints.

Read the full essay here.