Last autumn, geographer and green sketcher Ali Foxon joined Harriet and Rob Fraser at the LUNZ Hub event in Edinburgh. The ‘Land Use for Net Zero Nature and People’ Hub works at the interface between science, policy and practice, to support the UK in achieving Net Zero and other environmental and societal goals. This is a massive topic and a challenging task, involving many different stakeholders.

The PLACE Collective is involved as one of the LUNZ Hub consortium members (as we introduced in this blog here), working alongside other specialists within the Hub and stakeholders beyond the consortium. The Resonance project is one of the strands of work that has emerged from this – and in this blog, Ali reflects on her work within the Resonance team and shares some of the illustrations from the Big Dig Day.

Resonance and Illustrations – reflections from Ali Foxon

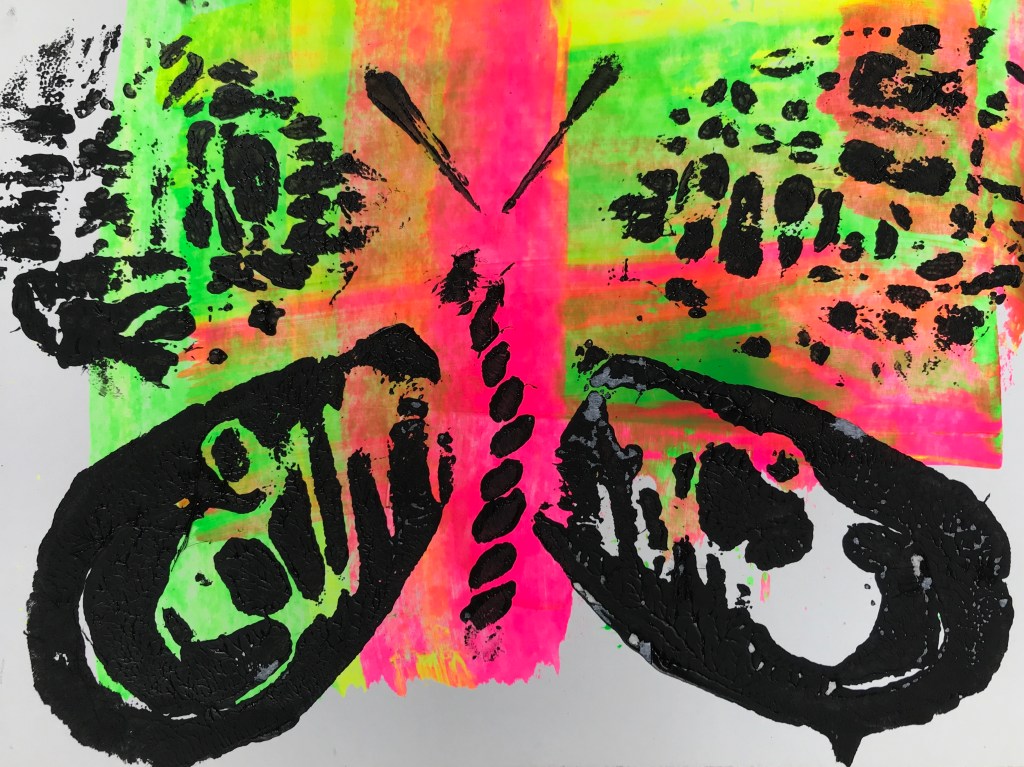

As an artist, geographer and founder of the green sketching movement, my practice is focused on observation and nature connection. I love opening people’s eyes to nature’s everyday beauty. That’s why I’m delighted to be participating in Resonance. The seven birch tree circles are going to become such beautiful living artworks as they establish and grow. At first glance, birch trees are quite unassuming. And yet, as you look more closely (with or without a pencil!), you soon see their striking bark, airy canopy, slender trunks, triangular leaves and spindly twigs; it’s hard to find a more elegant tree.

I believe real change depends on our hearts, not our heads.

When faced with so much fear, resistance and uncertainty, we must harness hope and possibility.

That’s why Resonance is so promising.

Ali in conversation in the village hall, at the Big Dig Day, November 2024

a boggy background

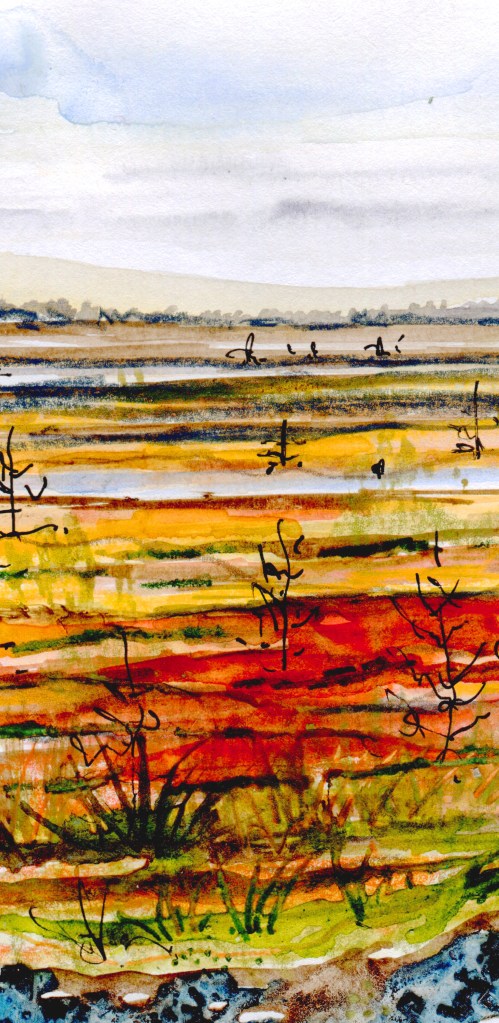

I’m participating in Resonance as an illustrator, albeit an illustrator with an unusually boggy background! As a young geographer, I studied peat bogs at Oxford and later I completed my PhD, funded by a consortium of UK conservation agencies, on the carbon consequences of habitat restoration and creation. I investigated the carbon impact of restoring afforested peatland among other things. LUNZ and Resonance have taken me full circle back to my boggy roots.

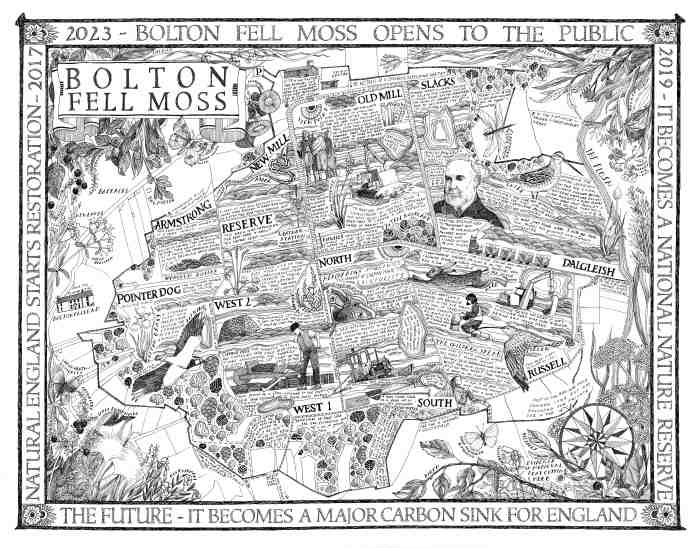

It’s been surreal and eye-opening tiptoeing back into an area of work I once knew so well. I’ve experienced so much deja-vu; so little seems to have changed. Obviously, we have made progress – not least the spectacular restoration of Bolton Fell Moss. Targets and ambitions have been refined. There’s much greater awareness about soil and forest carbon. And yet, we’re still bogged down in scientific uncertainty, regulatory frameworks, short-term projects, bureaucracy and lack of money; we’re still neglecting the importance of adaptation, wellbeing, social and behavioural change. This isn’t surprising. Land use change is such a hugely complex topic. But, at a time when we need rapid, urgent action, it’s hard not to conclude peat is accumulating faster than we’re making progress.

Hopefully, the LUNZ Hub’s work will speed up the process, bridging science and policy, generating the clarity and momentum necessary to accelerate change.

Yet, I believe real change depends on our hearts, not our heads. When faced with so much fear, resistance and uncertainty, we must harness hope and possibility.

That’s why Resonance is so promising. It’s already demonstrating the role nature connection and creativity can play in fostering the positive energy and conversations we need to collaborate and tackle the complex challenges of land use change together. I can’t wait to watch the magic and momentum of Resonance ripple across Cumbria and beyond in 2025. As for me, I’m looking forward to doodling more birch leaves, visioning beautiful futures and helping world-weary, nature leaders strengthen their creative resilience.

navigating challenges

For me, the beauty of Resonance, especially from a geographer’s perspective, is how the project’s heart and positivity extend through time and space, connecting so many different people and places. Resonance is drawing much-needed attention to peatland restoration, upland land use and the implications and challenges of meeting NetZero. But it’s also highlighting the immense value – intellectually and emotionally – of gathering outdoors, in-person, off our screens. As we navigate the challenging decisions that lie ahead, I hope the Resonance circles become treasured focal points for nature connection, symbols of care and gentle reminders that land use change can be positive, collaborative and beautiful.

Find out more about the LUNZ Hub here, and read about Ali’s practice here.