emma austin, natural england, in conversation with harriet fraser and rob fraser

It has been said more than once, and it’s true: it’s not possible to give a final ‘evaluation’ of the impact of a project until some time has passed. Arts interventions and multi-disciplinary engagement in community, scientific and conservation work have effects across a wide timescale: in the days, weeks or months in which direct research and engagement take place, and then in the months and years following that. Moss of Many Layers (MoML) is a case in point. So, 14 months on from the Wide Open Day celebratory event, we (Harriet and Rob) sat down with Emma Austin to hear her reflections.

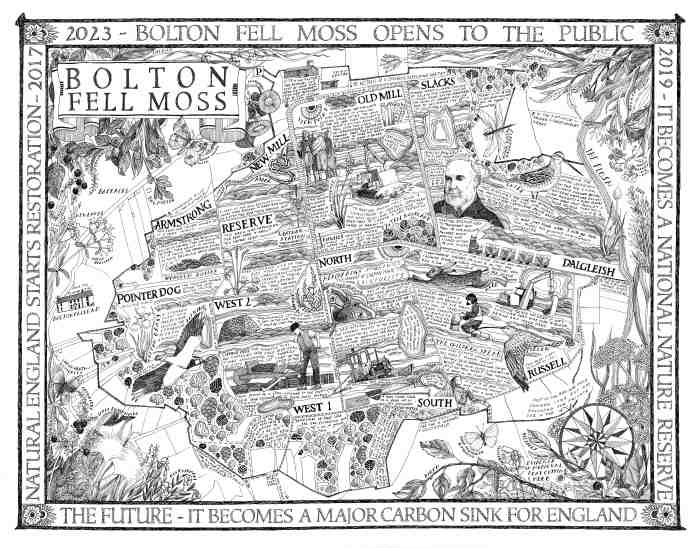

Emma, Natural England Senior Reserves Manager for North Cumbria, was part of the MoML project team. She already had an established relationship with Bolton Fell Moss – the vast area of peatland that is currently under restoration – and with some of the residents living around the edges of the moss before the project began. So what was the impact, or the novelty, of a project that brought together artists, scientists, restoration specialists, reserve managers and local residents? This was the first question we put to Emma.

What was the impact, or the novelty, of a project that brought together artists, scientists, restoration specialists, reserve managers and local residents?

Emma tells us that she really hoped the project would focus on the local community, helping to build bridges where people had been impacted by the difficult transition from an industrial site of peat extraction with local jobs and income, to a National Nature Reserve. ‘Having new faces that had no prior history with the place, artists who were independent, scientist with new knowledge, was brilliant,’ says Emma. ‘And the things that were introduced – whether it was a camera, a poem, specialist kit – these were new, and fresh, and I think the local community who became involved perhaps felt involved in a way they hadn’t been before.’

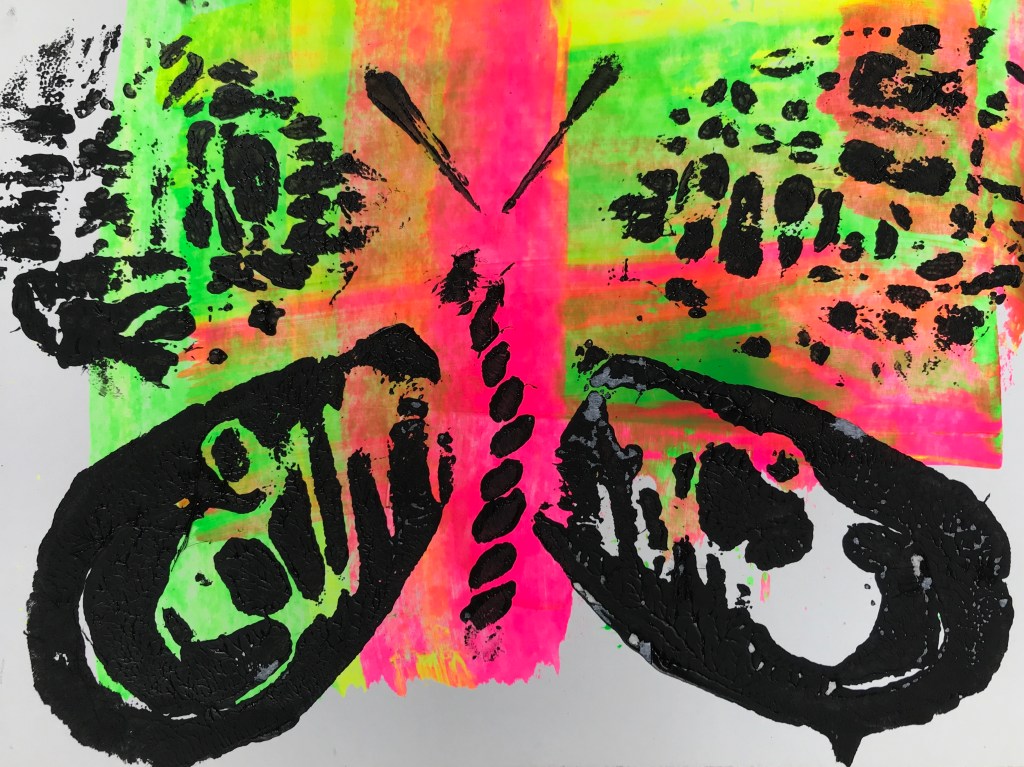

Emma taking part in the schools events, co-designed with artist Anne Waggot Knott

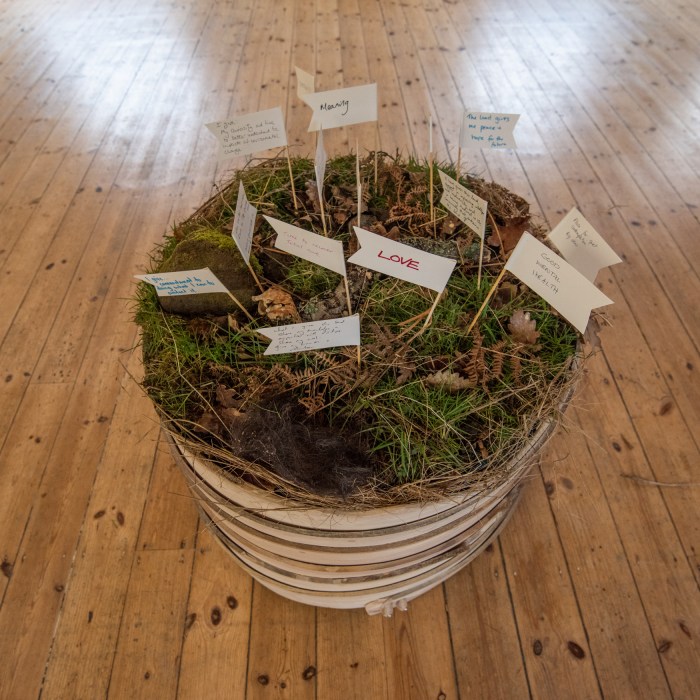

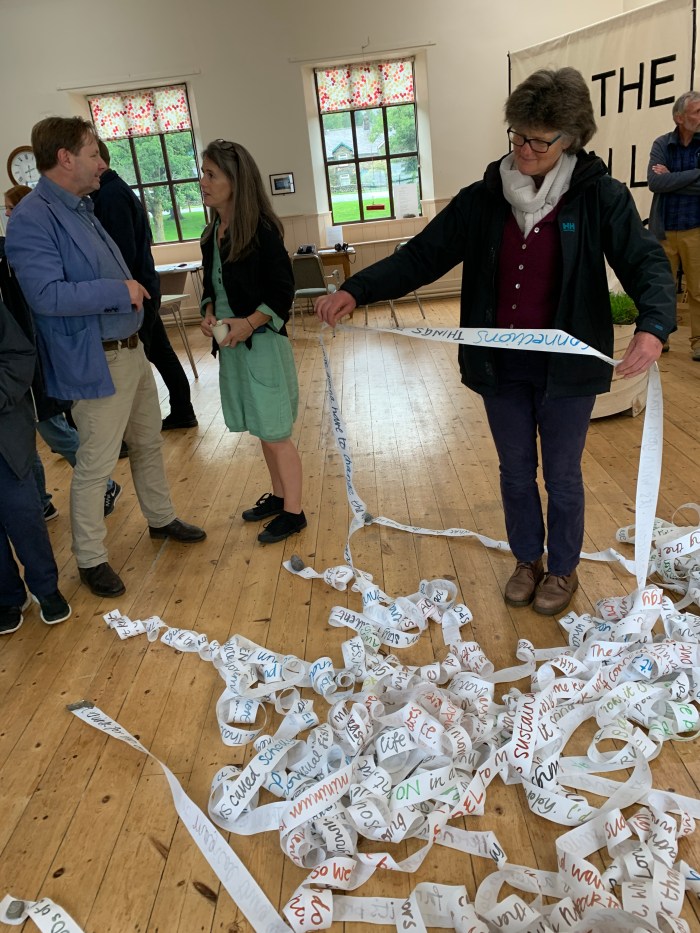

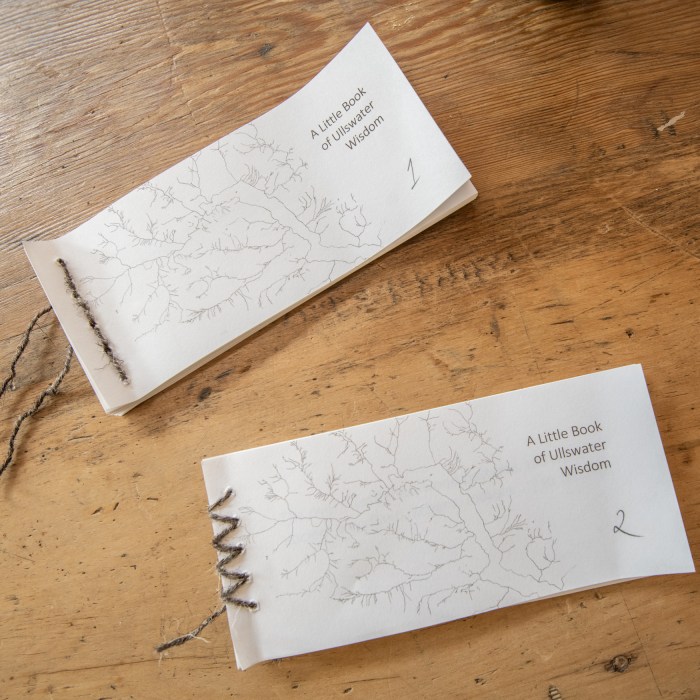

Emma says that she senses the project’s impact through the new links made with the local community. The first time this hit home for her was the huge turnout for the Wide Open Day. Emma always grins when she talks about this: the peat core extending the length of the hall, the room buzzing with conversation, curiosity about the artworks, school children and their parents, and local people meeting one another, some for the first time.

Emma tells us there has been a real growth in interest in the moss since then, nicely coinciding with the completion of the new 3km boardwalk. Juliet Klottrup’s film has been a feature at local discussion events, and there is a definite interest for more of these. The mailing list for news of Bolton Fell Moss has grown fourfold; and events on site run by an engagement officer over the summer were really popular.

In June 2023, during a nationwide heatwave, there was a fire at Bolton Fell Moss, and for six days people worked together to tackle it.

In June 2023, during a nationwide heatwave, there was a fire at Bolton Fell Moss, and for six days people worked together to tackle it. ‘It sounds strange,’ says Emma, ‘but I think the fact that we did the Moss of Many Layers project may have made a difference. I certainly felt able to ask for help in a way I would have been wary of in the past. It’s hard to say for sure that this is linked with MoML, but the project may well have played a part in the way it helped create new friendships and familiarity.’ The intervention of artists helped to bring people together, and the continuing use of the film in Emma’s meetings helps to spotlight local people who are connected with the moss – who live nearby, who once worked there, who are engaged in monitoring, or just love to visit, and who have stories to share.

Emma smiles as she talks about the poem signs on the bog. She often hears positive comments about them, and just last week she heard from a group of MSc students who had said they loved the poem and had a WOW moment when they learnt that the signs are anchored and so they will act as a measure of peat accumulation for centuries to come – a novel combination of art and science.

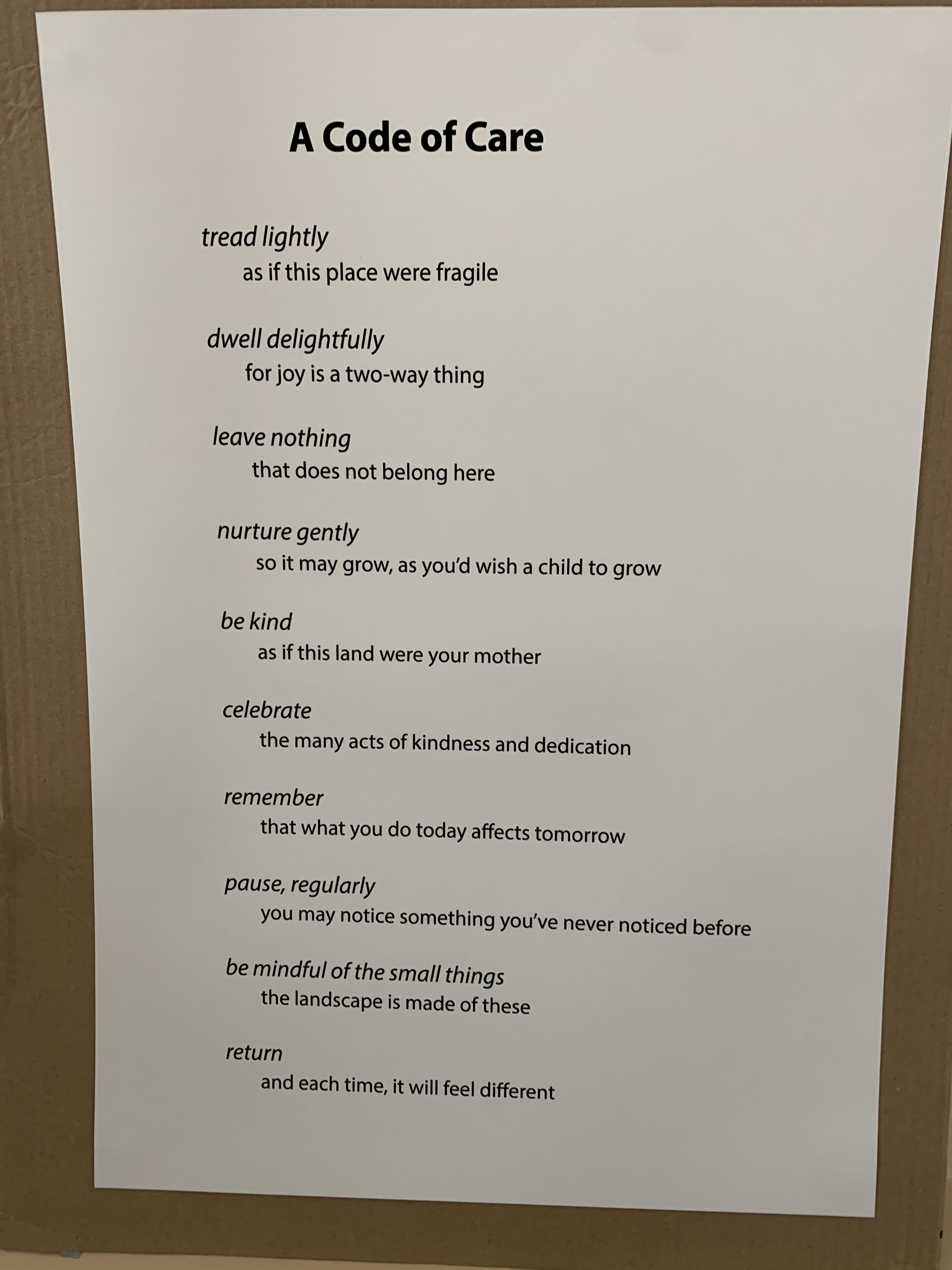

‘People get used to seeing things in a certain way,’ says Emma, ‘We all do. But seeing it from a different perspective – through the arts – can bring a different outlook.’

One of the central elements of Emma’s role with Natural England is to get to know people and liaise with land owners and farmers about changes that are needed to support restoration of the moss. Emma thinks that the inclusion of art, and the presence of the artists and scientists in the area during the project, has helped people understand the bog more and feel the importance of it, and has also helped to soften the edges of difficult conversations. ‘People get used to seeing things in a certain way,’ says Emma, ‘We all do. But seeing it from a different perspective – through the arts – can bring a different outlook.’

For her, the Moss of Many Layers project helped, above all, to put the community first. ‘How do you make sure that you create a discussion or a conversation where the person whose place you’re in feels as important, or the most important, part of the jigsaw. Because if we are going to achieve any of the things we want to achieve for nature, we’ve got to involve everybody – and the way the Moss of Many layers brought different strands together, through art and science, helped to create a neutral space of shared ownership.’

‘… if we are going to achieve any of the things we want to achieve for nature, we’ve got to involve everybody – and the way the Moss of Many layers brought different strands together, through art and science, helped to create a neutral space of shared ownership.’

For more on Moss of Many Layers:

Visit the main project page here.

Also tap into these blogs about the process, including work with schools, the Wide Open Day, Scientist Jack Brennand’s reflections and you can use the search function, looking for Moss of Many Layers to explore further.