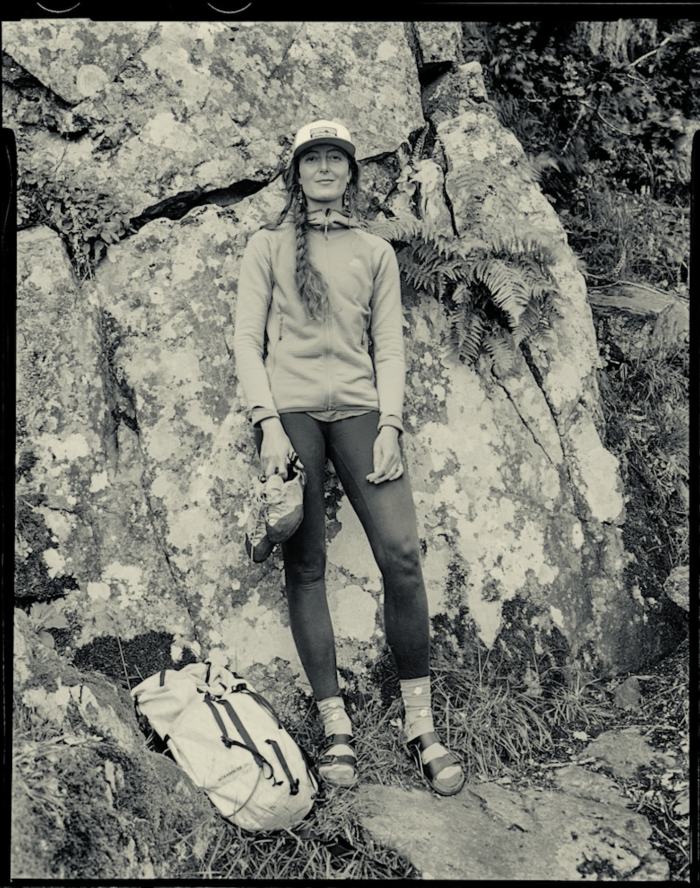

Daksha Patel is one of the artists involved in the Creative Collaborative Placement scheme with the LUNZ Hub. Daksha is liaising with the Rothamsted Research institute, following a line of enquiry beginning with a focus on supporting agroecosystem transitions in the context of a changing world.

In this blog, Daksha shares her experience at Rothamsted Research, her engagement with the institution’s ‘Farm Platform’, activities with staff, and emergent insights and questions. (To find out more about Daksha and her placement overview, visit this blog here).

Visiting Rothamsted Research Farm Platform

My visit to Rothamsted Research, North Wyke, was pivotal in understanding the vast scope of the work at the world’s most instrumented ‘farm platform’. It is part farm (arable and livestock), part science living laboratory, and part data collection. I was surprised and delighted to find that the team is very international, which was unexpected in a rural setting near Dartmoor.

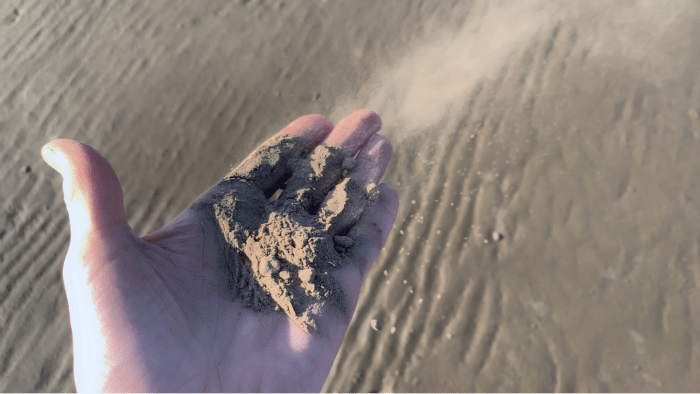

The work at Rothamsted Research broadly consists of testing, experimenting and measuring the impact of different farming practices upon climate change, biodiversity, soil health, emissions to water and air, and food production. Ultimately, their research feeds into developing farming policies within the wider economic, political, environmental and social contexts of the UK: important work given the impact of farming on the environment.

Learning In Place

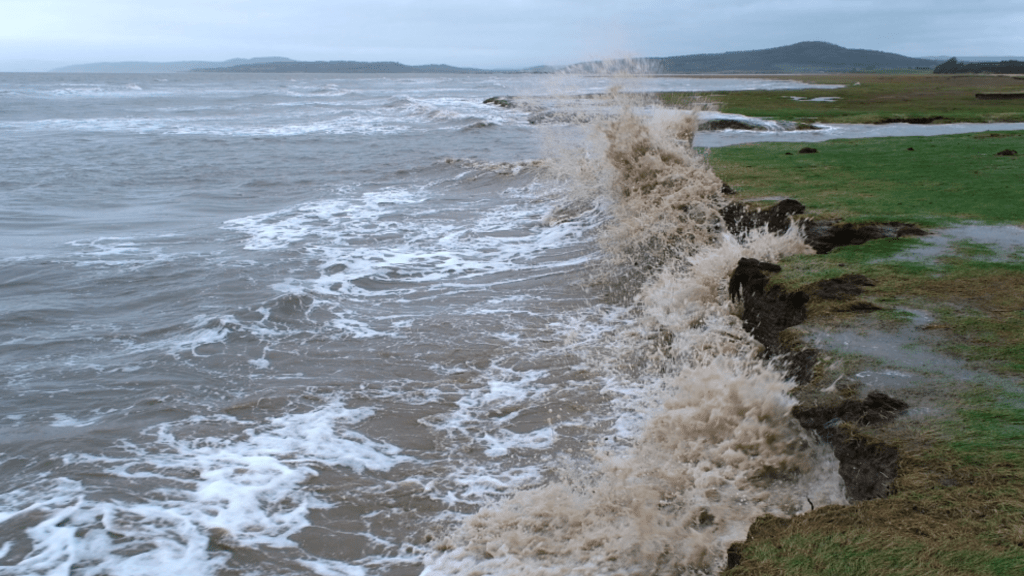

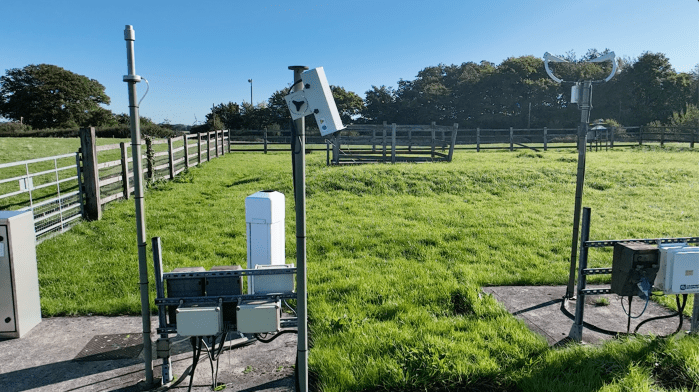

My first day was spent looking around the different experimental sites with science technician Chris Powe whilst capturing some drone footage – this was the perfect introduction. I was shown the biomass plots, the weather station, farm buildings, livestock and crops. Each field on the instrumented North Wyke Farm Platform has an array of sensors; some measuring the water quality of the run-off, others collecting the levels of greenhouse gases emitted from the fields or data about soil moisture content. Samples of soil and water are collected regularly; drone footage is used to measure the growth rate of different crops.

The scientists at Rothamsted Research North Wyke are working on a variety of different research questions. Prior to my visit, I spoke online to a few and subsequently explored how I could bring key ideas from our discussions into a creative workshop during my visit.

It struck me that everyone at Rothamsted Research

is asking different questions about farming practice

– often really complex multi-layered questions

with no easy answers.

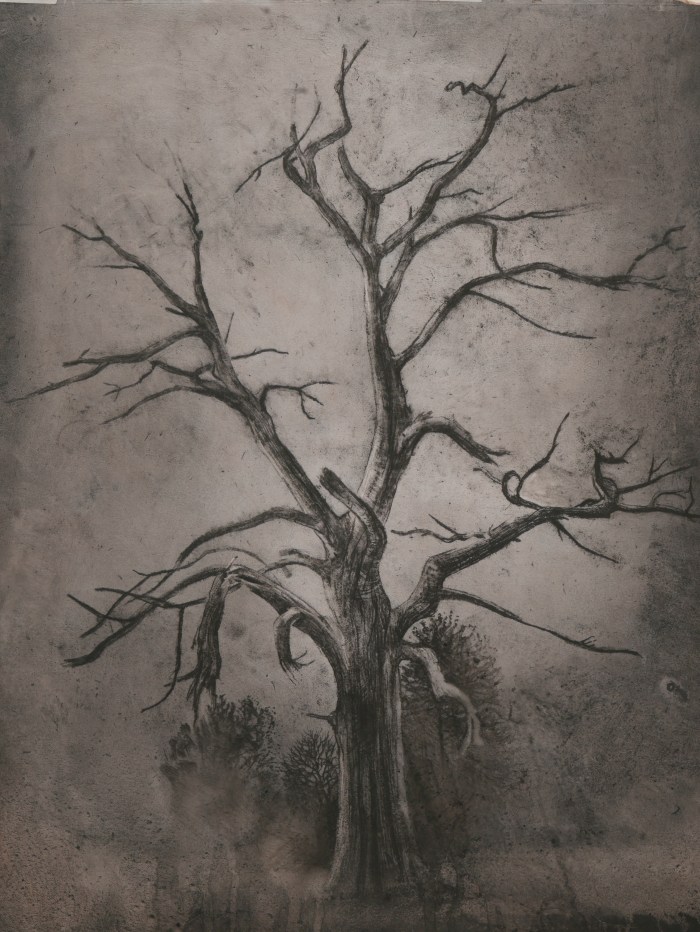

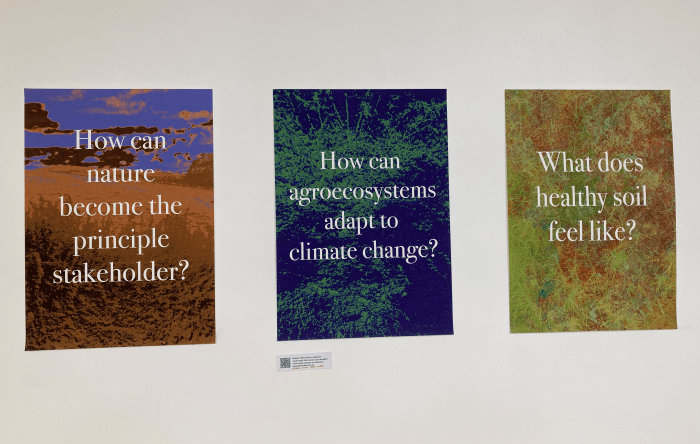

It struck me that everyone at Rothamsted Research is asking different questions about farming practice – often really complex multi-layered questions with no easy answers. The notion of questioning became the catalyst for the creation of my first artworks – a series of ten digital prints. The use of text in conceptual art is often associated with social and political commentary, and this format seemed appropriate for this work. The questions were deliberated over time, and I think of the artworks as ‘print provocations’ because they are a stimulus for discussions, rather than questions that can easily be answered. They are open questions which are interrelated – they probe and enquire without fixed parameters and they enquire about the senses as well as the brain. The prints merge text with images of Rothamsted Research that have been edited to create a highly pixellated and colourful data visualization aesthetic to refer to data collection and modelling processes.

The questions are open questions which are interrelated – they probe and enquire without fixed parameters and they enquire about the senses as well as the brain.

Questions as Starting Points: the ‘Adaptations’ Workshop

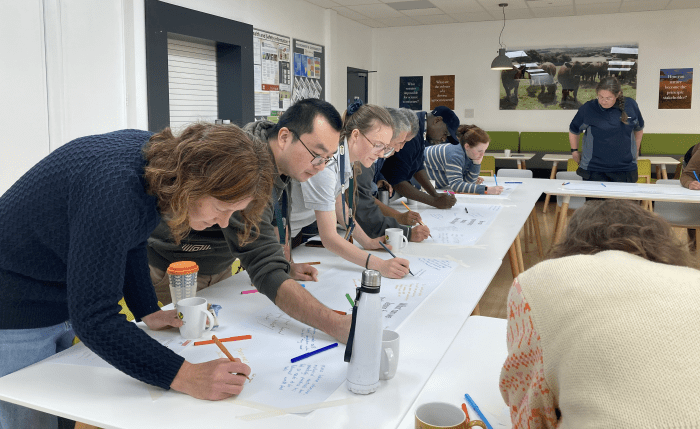

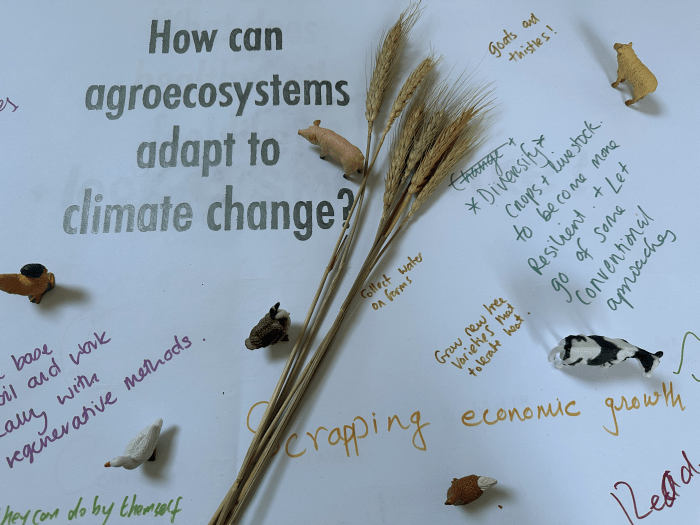

The prints were installed in the canteen at Rothamsted Research North Wyke with QR codes to enable all staff to add their responses online. The questions became a starting point for a workshop. In my practice, a creative workshop often comprises some key elements – it brings people together in a playful and reflective way, there is energy and movement, and of course a creative activity. A workshop is less focused on teaching people ‘how to paint’ and more on the dynamics of a group coming together. This was particularly important at Rothamsted Research because I had learnt that they don’t often have an opportunity to do this.

The workshop was titled ‘Adaptations’ and began with a quick-fire writing activity in response to the print provocations. We had some wonderful responses such as: ‘Good farmers are engineers and polymaths, they know loads of stuff about a range of disciplines’ and ‘Healthy soil is like chocolate cake – dark, full of life, smells good, structured, aerated.’ A group discussion naturally followed this, with some really interesting thoughts upon what gets lost in translation from science to policy.

… some really interesting thoughts upon

what gets lost in translation from science to policy.

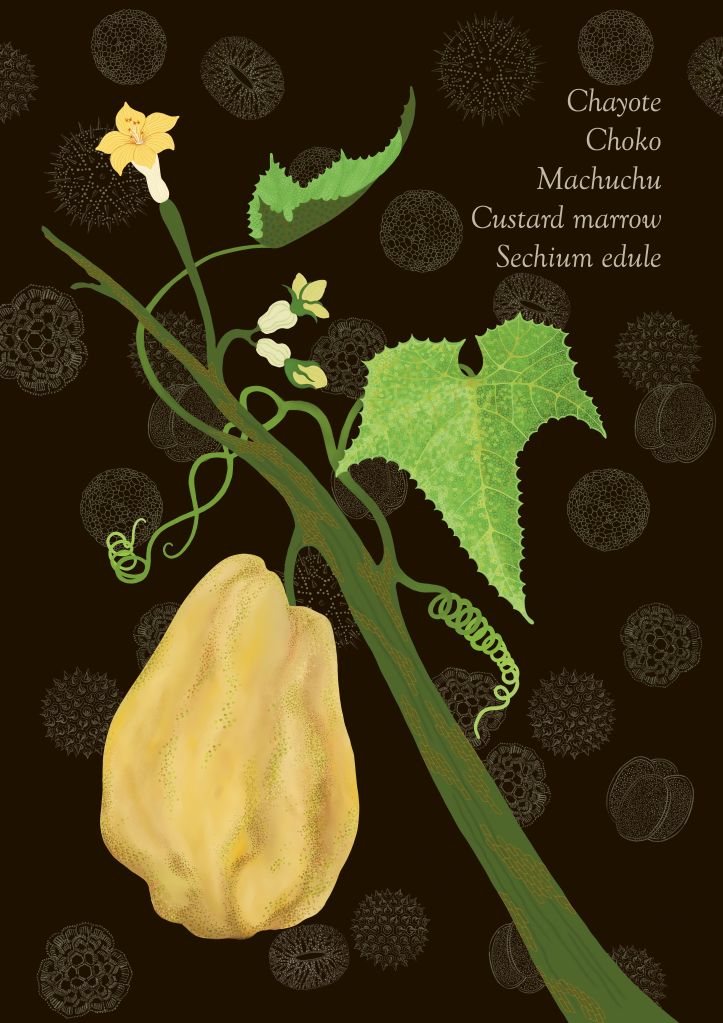

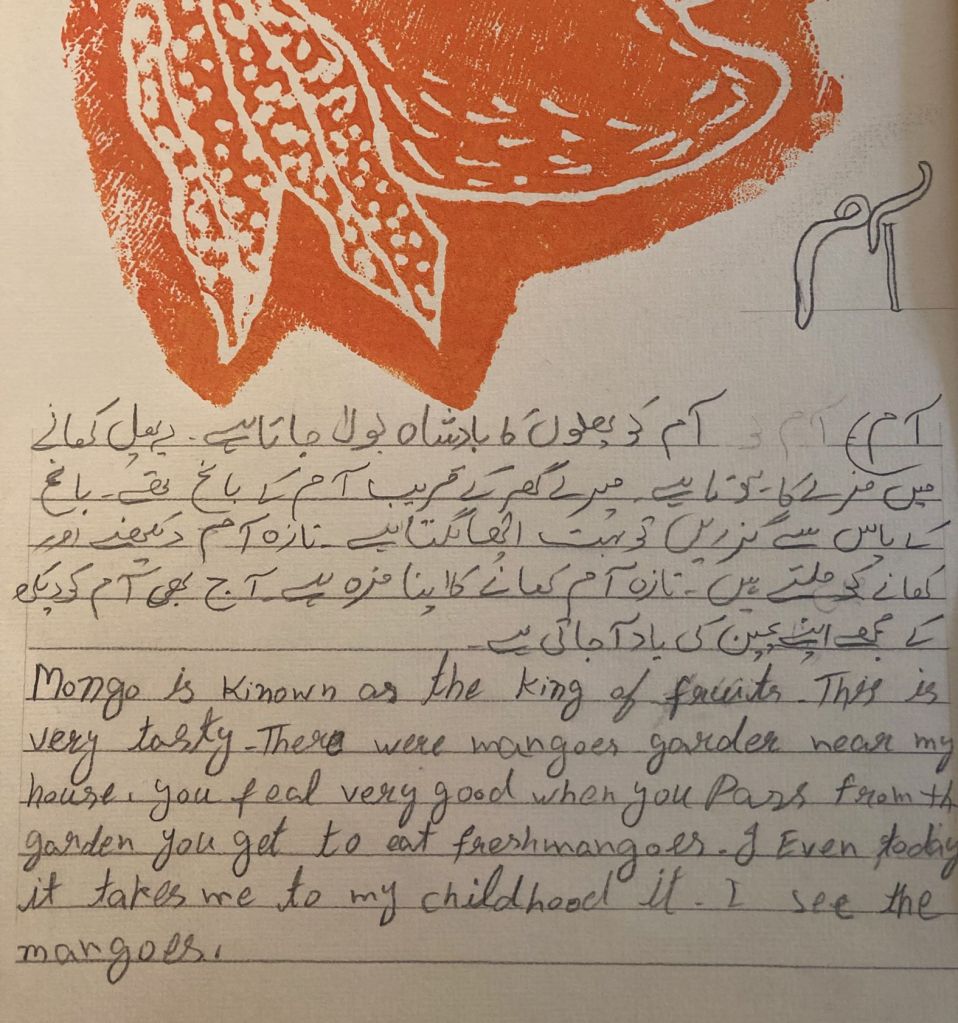

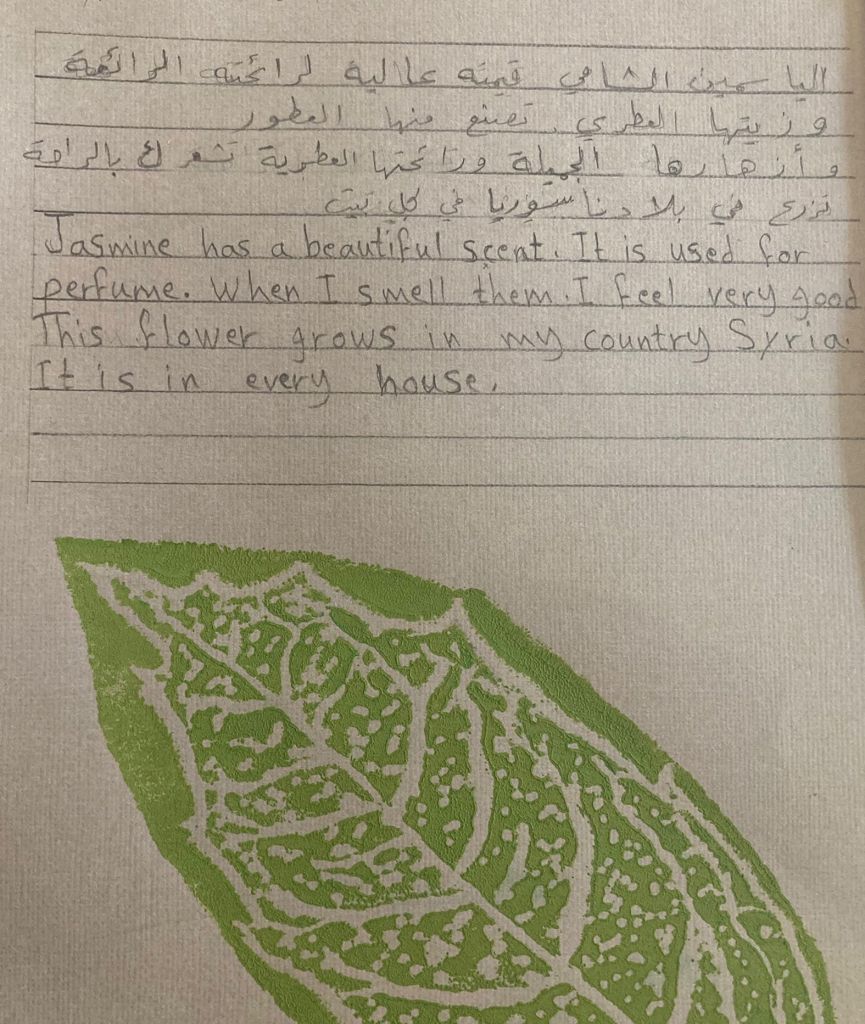

Next, I asked participants to choose an object from a selection of vegetables, fruit and cereals grown in the UK and some toy farmyard animals. They were asked to write a short text from the position of their object by telling humans what they needed to thrive. This darkly humorous piece is written from the position of an onion: ‘If you see it from my perspective, things are pretty dark & gloomy. Not just because I am mostly underground with the soil, but because you always choose to exploit the system for your own personal gain. Even if you think it’s for others, it’s always your choice. I am rooted in this earth. I am reaching for sunshine and growth. I am a big fat acidic layered being, and I don’t want to be ripped from my home and put in a korma, which inevitably ends up in the bin.’

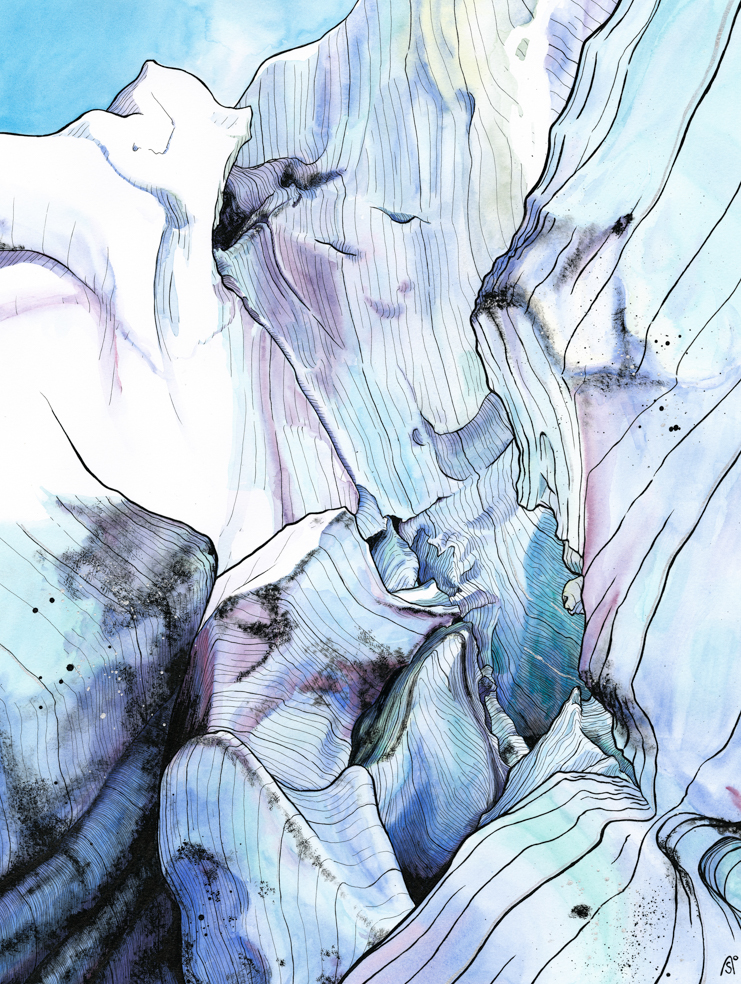

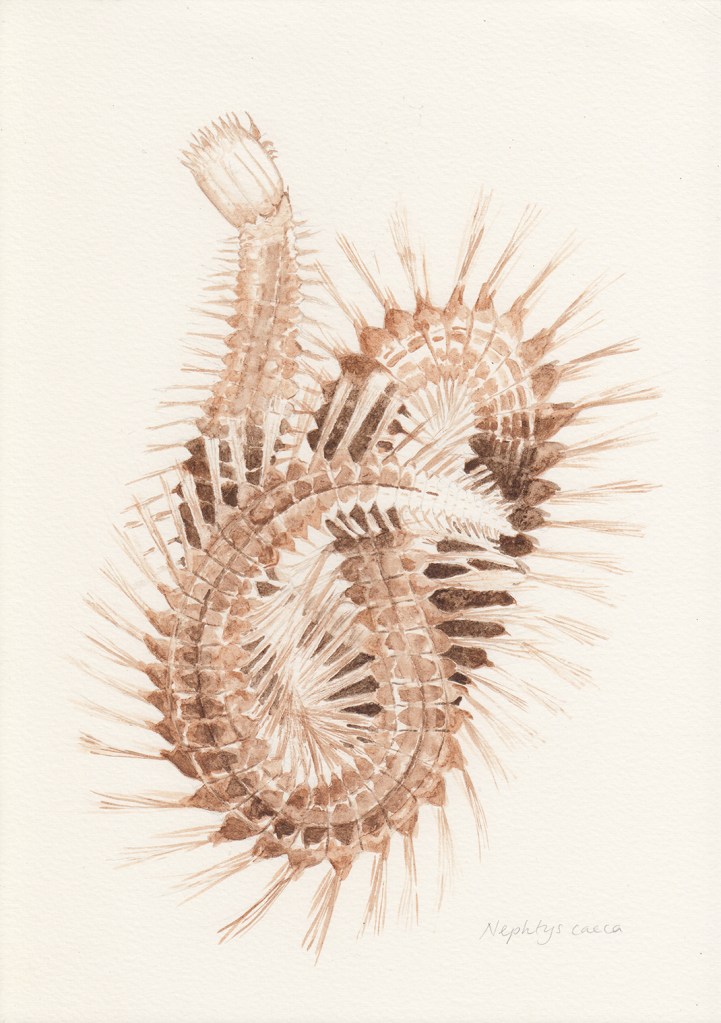

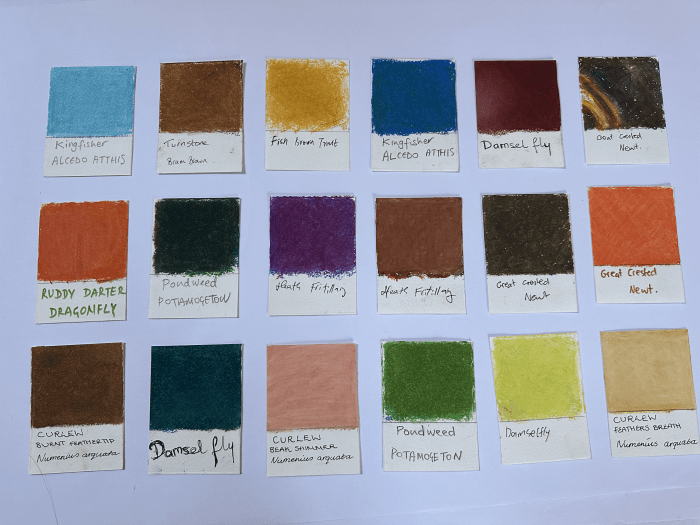

Lastly, we looked at some photographs of species of flora and fauna that are disappearing from the UK landscape as a result of farming practices. We explored if their loss deprives the natural world of a spectrum of colours (this article makes interesting reading). Next, I demonstrated how to create colour samples using pastels by isolating sections of photographs. I often find that the richest conversations happen when people are immersed in a creative activity. There was a lovely buzz in the room as people settled into mixing their chosen colours.

I often find that the richest conversations happen

when people are immersed in a creative activity.

Prior to the workshop, a few scientists expressed a desire for the print questions to be clearly and empirically answerable. By the end, the conversations reflected a higher tolerance for ambiguity and multi-layered answers. Given the complexity and interconnected nature of their research, ambiguity and flux are inevitably part of the systems they are measuring. Artistic practice typically has a high tolerance of ambiguity, and this is perhaps the most valuable thing an artist can bring to this environment.

In Daksha’s next blog she will talk about her visit to a farm in Dartmoor.

For more about Daksha’s placement focus, visit this blog.