One thing rings true, repeatedly. We need to connect again, not with the internet but with ourselves, our families, our earth. Perhaps this gathering of people and art practices is just the antidote we need.

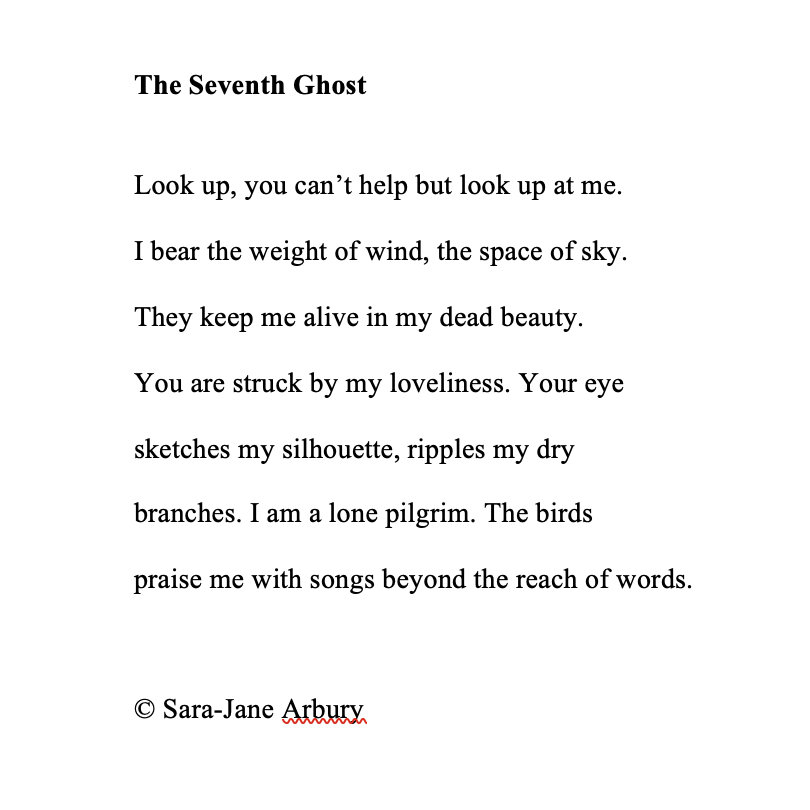

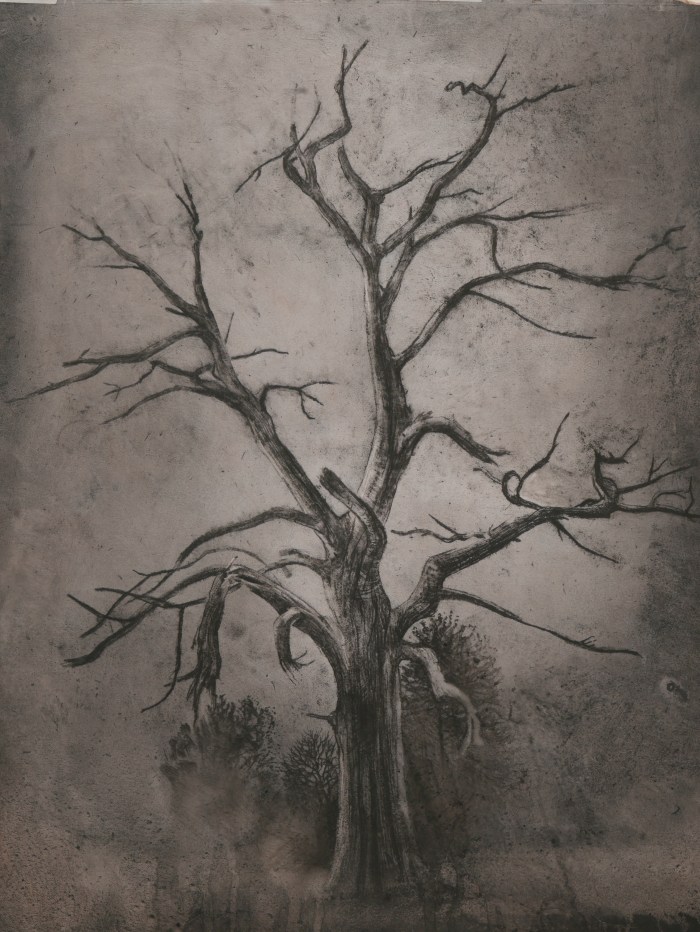

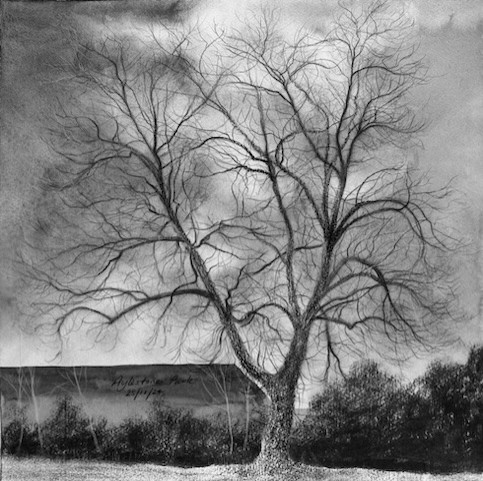

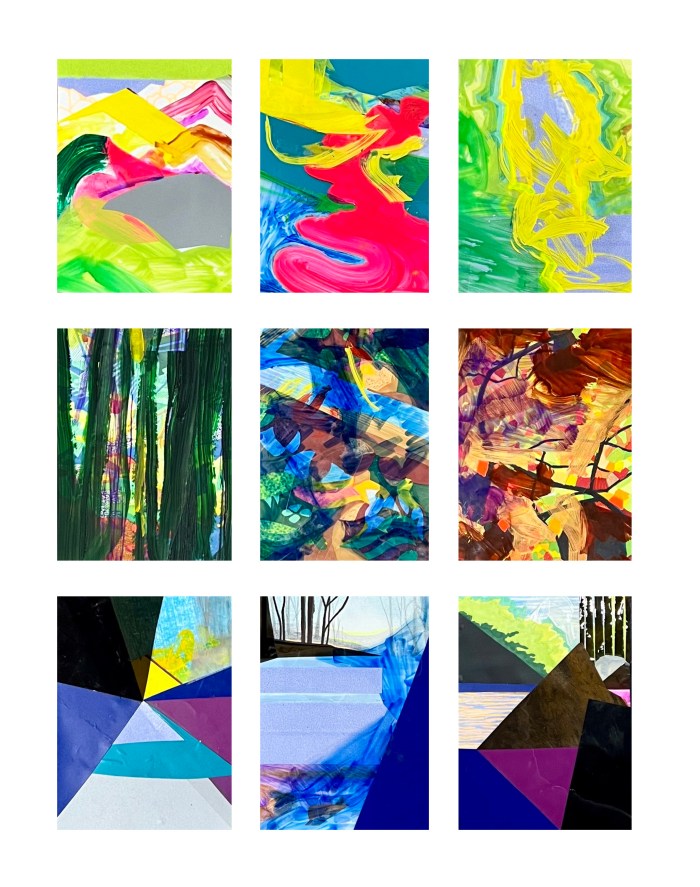

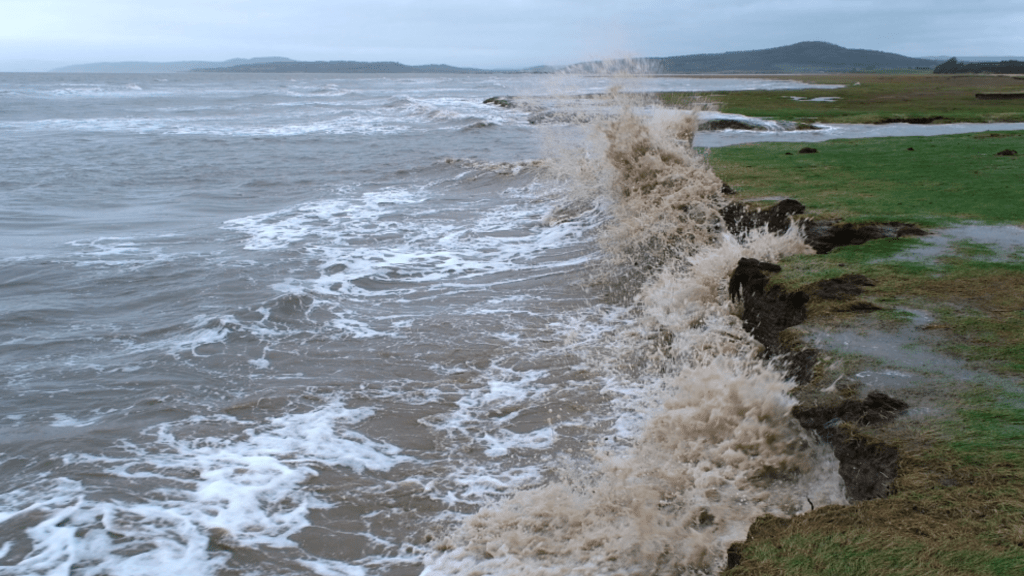

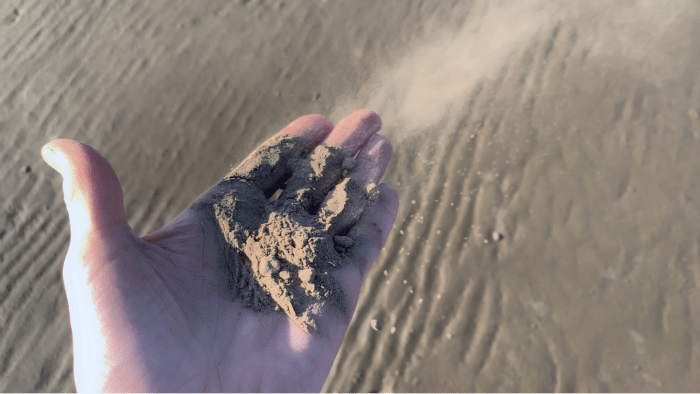

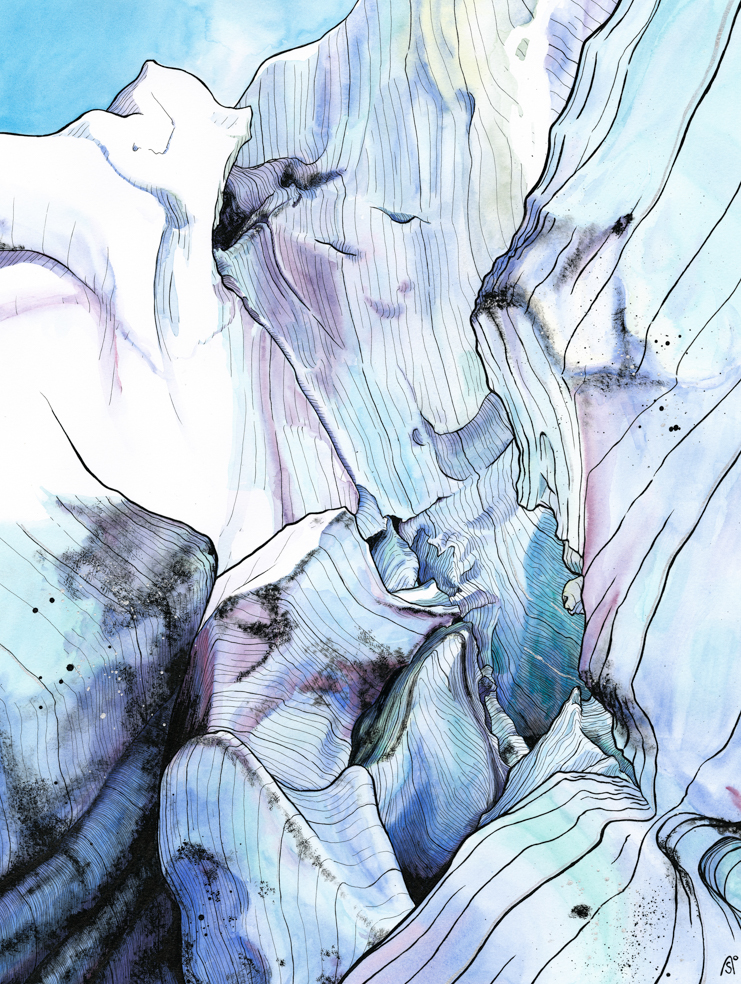

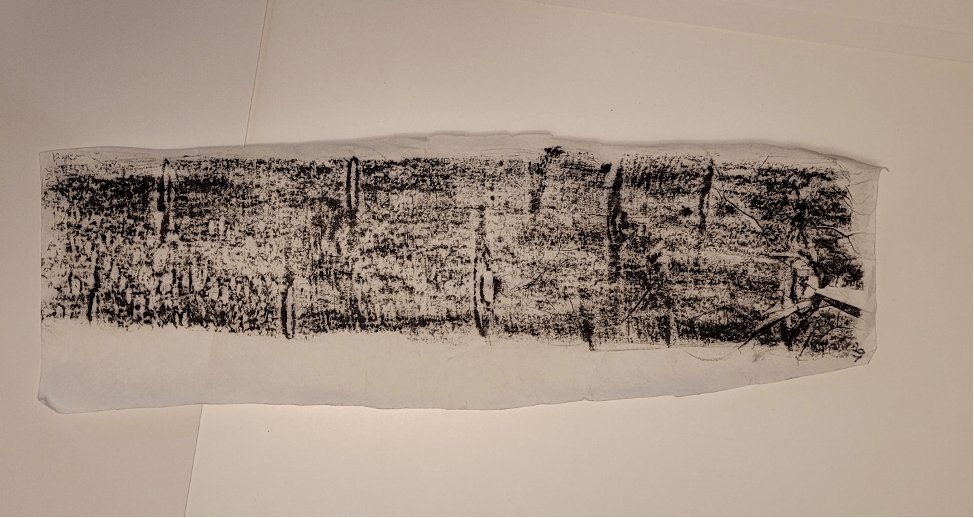

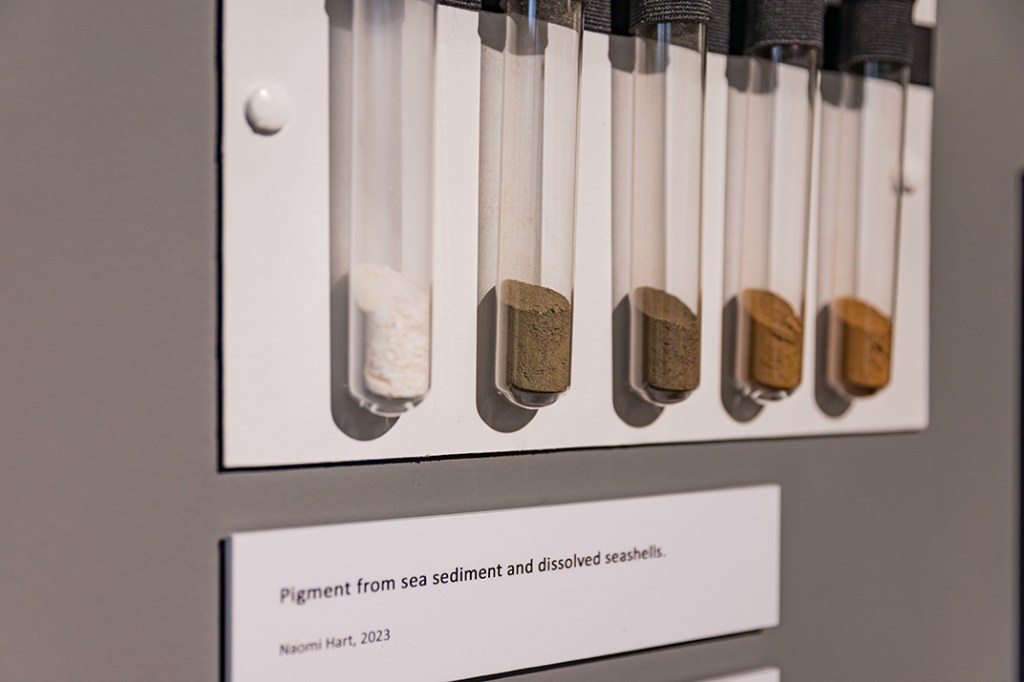

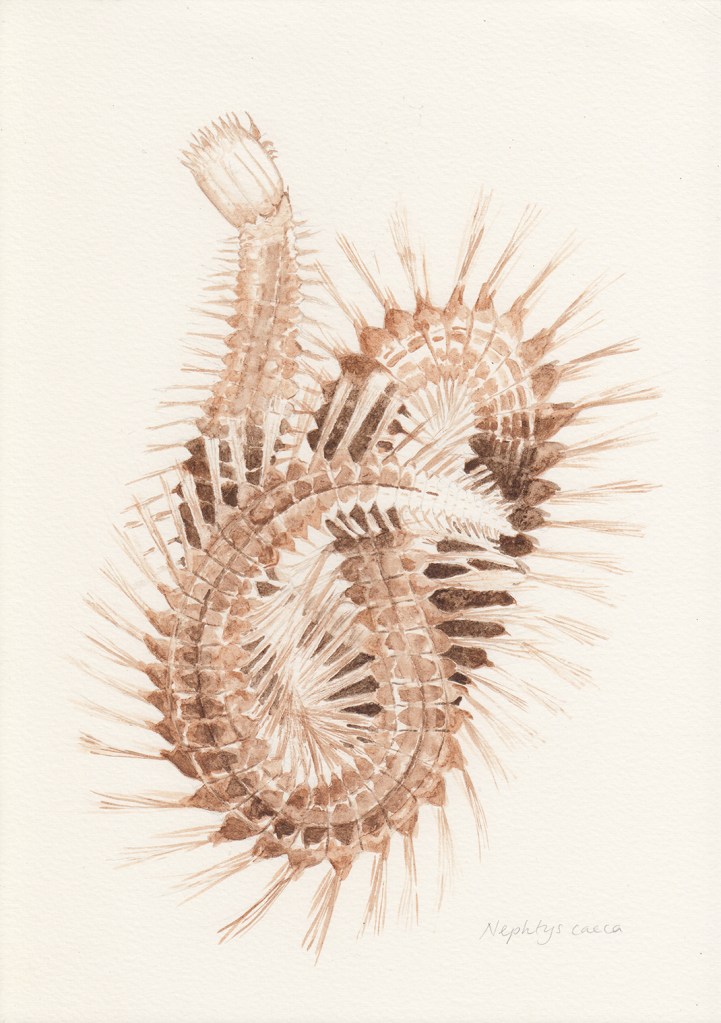

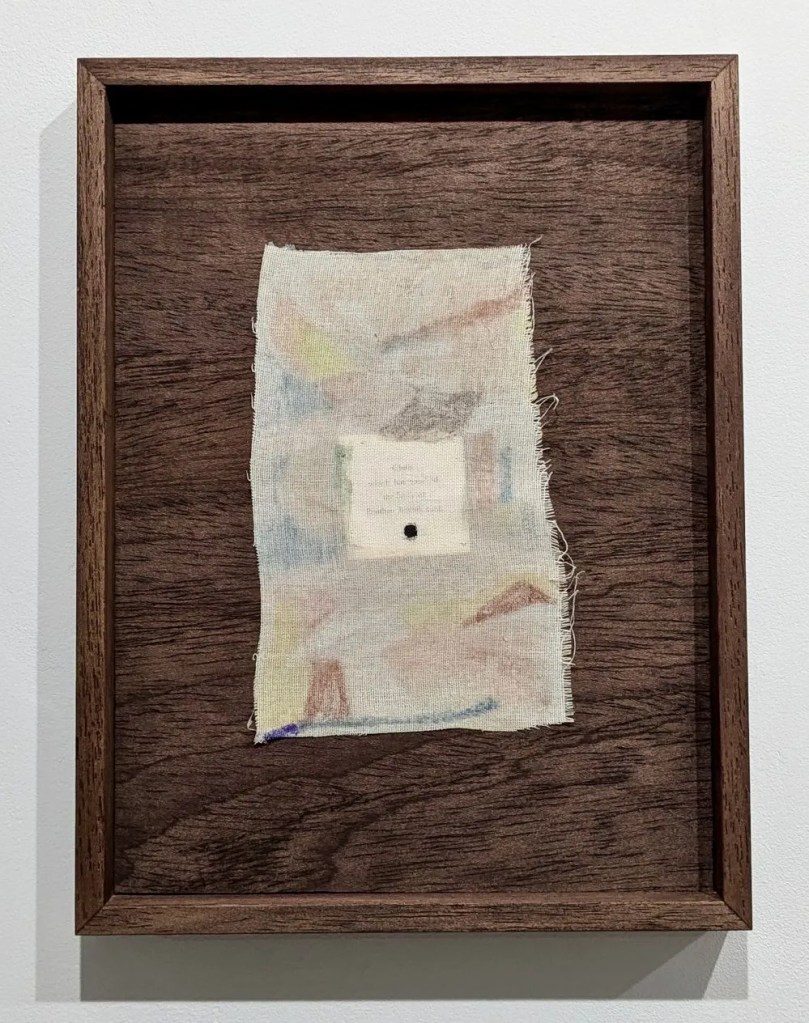

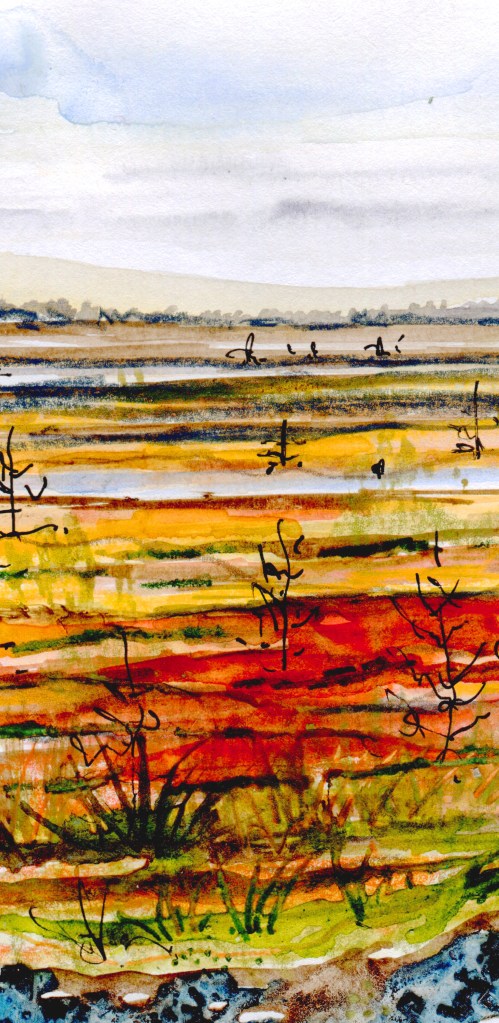

It is amazing to be part of the PLACE Collective, and to be one of the exhibiting artists contributing to ‘See Here Now‘. The exhibition brings together work from artists exploring our connection with the planet, the earth, the land. It’s not a ‘pretty’ exhibition – it’s an exhibition asking, investigating, celebrating, hurting – responding to our relationship with our home, and who we are within it.

The exhibition launch coincided with a gathering of PLACE Collective members, with networking, talks and workshops, at Grizedale, and of course, I went along. The day was curated by a PLACE Collective panel – curated beautifully with creative, insightful and embodied interventions to explore and stretch our thinking and our ways of being.

Having attended a previous PLACE Collective gathering in 2022 I really enjoyed reconnecting with some familiar people – we’d already sparked conversation (and creative friction) in that residency and the ground was prepped for new ideas to emerge. It was also brilliant to meet new members, adding to the tapestry of creative insight and igniting new thinking and new energies.

We connected in different ways throughout two days, beginning with a thinking framework that was beautifully proposed, and gave space for input and replenishment, with thanks to Wallace Heim.

We broke into small groups for some critical thinking inspired by the suggestion of the five themes, and then came back together to discuss the main insights. It was intense! Our brains needed recuperating after that, and a somatic movement session with Jools Gilson was such a wonderful, reconnecting treat. We explored our own sense of space, body and movement, working in pairs and then in sets of four to create an immersive ‘performance’.

The results surprised us all – and led to a lot of smiling and laughter. The elements came together in such an exciting way, one exercise building on the last in gentle momentum until the final delight of sharing and bearing witness to each other’s. Reconnecting with self in this way is a strong reminder to ground ourselves and strengthen our sense of who we are in connection with an other … I’ve since repeated elements of this practice you’ll be pleased to hear Jools!

Our conversations over coffees and lunch were expansive, deep and uplifting – bringing together an eclectic mesh of minds, and refuelling us in a space full of warmth and generosity of ideas.

One thing that brings the group together is the research element of practice. The questions posed by Wallace provided deep reflection and I’ll use those in my own research and explorations.

sowing seeds and energy

The PLACE Collective continues to become a rich field by which seeds can emerge and flourish … a network of nodes bringing many elements to view, and a platform by which to ask, enquire, analyse, propose.

Needless to say, I came away filled up – new lines of thought, connections and my own ‘nodes’ coming together, a reflection on my own practice and a community of inspired and rich minds who generously contributed to the space that is the PLACE Collective.

There are so many other networks and industries that can tap into this energy, this beautiful collective. Here, it feels the soil is being well prepared and becoming fertile for ideas and connectedness in a way that will sustain and be resilient to the world’s collective anxiety, that so many people are feeling just now. And the atmosphere feels open and embracing – not at all exclusive.

It feels the soil is being well prepared and becoming fertile for ideas and connectedness in a way that will sustain and be resilient …

As well as practising as an artists, I’m a leadership coach. I see on a daily basis the struggles that people face, linked with issues such as climate and political threats to humanity, as well as the consequences of sustained desire for commercial, capital, profit and ‘more, more, more’. These manifest in our lives and in our work places, and in our families, as burnout, overwhelm, procrastination, numbness, addiction, mental health epidemics and dis-connection. I often coach as much on ‘how to deal with things’ as on how to make the kind of impact we want to see in the world.

One thing rings true, repeatedly. We need to connect, again, not with the internet but with ourselves, our families, our earth.

Perhaps this gathering of people and art practices is just the antidote we need.

Thanks to Kate Gilman Brundrett for sharing her reflections after the members gathering in April 2025. You can find out more about Kate’s practice here.